For as long as I’ve lived and fished in the Northeast, November has been uncomfortable. There are certainly worse times to be an angler here, but late Fall’s rapid transition from good to sub-par angling opportunities always has a bit of a depressing element. Broadly speaking, this is a time when fish spawn, migrate, or drastically change their feeding habits, and bites you until recently took for granted fizzle out in a matter of weeks.

Long story short, the season of the grind has begun.

As Autumn fades in Boston and I head into my first New England winter in three years, this change is noticeable and well in motion. Local striped bass are currently out of fly range. The miles of high density carp water I could hit from my apartment are empty, with all of the fish ditching the shallows for deeper wintering zones. And with Massachusetts (along with much of the region) facing significant drought conditions, the trout streams are skeletal.

In my last few seasons in Oregon, the winter blues were vaporized by highly productive trout opportunities that offered some of the most exciting fishing of the year. I already know that this will be hard to replicate, but the eastern season of the grind has some upsides as well. It invites curiosity, research, and a rare, addictive reward. With much still to cover with a fly rod, these next unsavory months are no reason to stop exploring. Here’s what I’ve been up to as the season begins to slow:

Carp Finishing Move

Success is when preparation meets opportunity. In this example, I turned on an opportunity, did a rubber-burning sieways drift around preparation, and still somehow pulled it off.

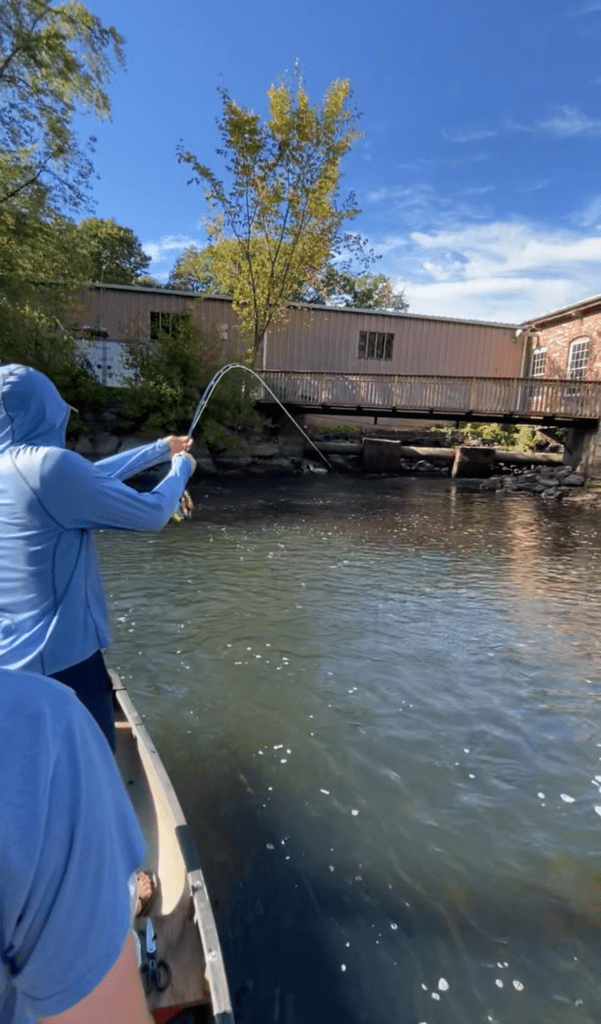

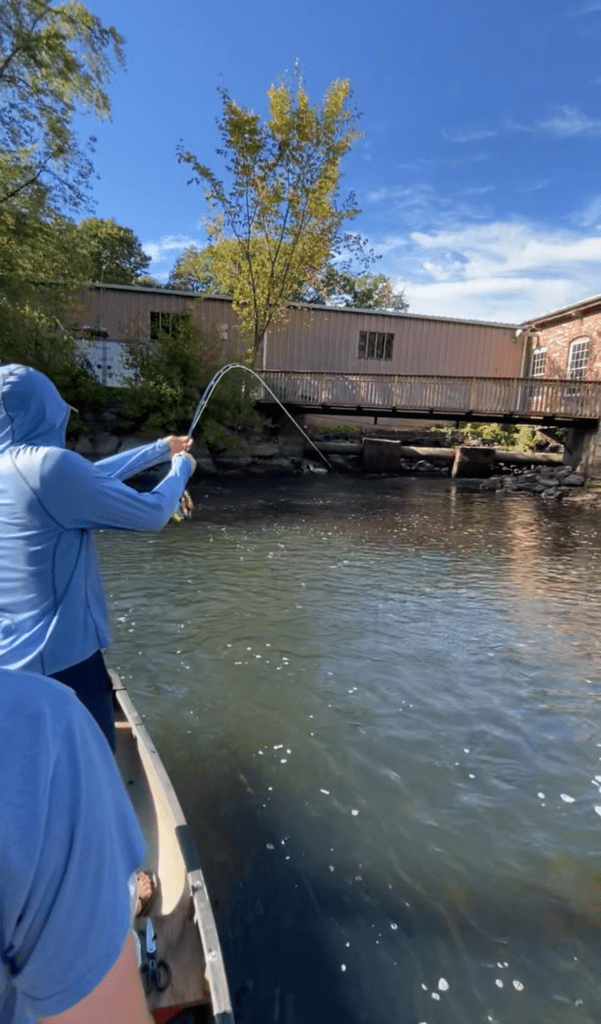

Jon, Charlie, and I were pike fishing. We loaded Charlie’s big red canoe into a Merrimack River tributary and started our drift underneath a little spillway, prepared to fire off big streamers at thick cover for the afternoon. Fall was in full swing, and the water was low and clear. As we hit the top of our drift, we noticed a few carp piled into a large crater in the riverbed. They spooked as we went over them, but not before we got a good look at their size— There were some big ones in there. Our summer had been filled with carp, and we were already set on chasing pike, so we logged the encounter and moved on.

Several hours later, we had a change of heart. We’d found a few pike and had been followed by some bigger ones, but the day had been very slow overall. Going back for the carp had started out as a joke (30 minutes of silent casting broken by “I bet those carp are feasting up there right now…”), but as we reached the end of our long paddle back from the car, we chose revenge.

The only barrier was we’d been so set on pike that all we had were pike setups— Ten weights and intermediate line. Although I was able to fashion a 3x tapered leader out of some spare spools at the bottom of my backpack, my current rod would protect it about as well as a broomstick.

Not to be discouraged, up we paddled, stealthier this time, to the carp hole. The fish had reset and were happily making their rounds on the sandy bottom. I browsed through the only non-streamer fly box in my pack and settled on a small beadhead egg, tied on a size 16 jig hook.

I use this app to play fantasy football with my friends. Each week the matchup rundown features a win probability, which fluctuates depending on players’ projected performances and their current status. As my eyes traveled from the trout pattern and up my eight pound tapered leader, then down the monstrous ten weight in my hand and over the side to the large fish below, I wasn’t liking my lineup if I actually hooked something.

It took a minute to perfect the technique. The ten weight casted the light leader and fly like it wasn’t even there, and the intermediate line dragged in micro currents as it slowly worked its way into the depths. In around ten feet of water, the carp didn’t seem to mind the commotion of a few failed drifts, and I was soon rolling my egg rig across the bottom. To my surprise, on a cast that brought the egg towards the center of the pool, a large carp broke off from the school and picked up my fly.

I didn’t really set, afraid that a hard hit on a heavy fish in fast current would break the tippet immediately. I kind of just lifted up slowly and hoped that the small barbless hook would find its place as the fish turned. The carp started its first lumbering run, zipping across the pool and towards a rock pile at the back that I knew would be difficult to turn it from with my setup. My win probability took a dive as I applied the lightest amount of side pressure and attempted to gently coax the fish back into open water.

After warding off several more attempts to exit the pool, the fight entered another stage. The fish rolled around in the depths right off the boat, bouncing off of boulders and trying to duck under ledges. Even the fact that the carp was still on, which should have offered reassurance, became stressful. In the early seconds after the hookset I assumed the fish would quickly break off or the hook would bend out. Now almost ten minutes later I was actually starting to believe we could land this thing, which suddenly gave me something to lose.

I finally had the fish in a route, carefully controlling its tiring runs through a safe path as I worked it closer to the surface. Its massive head broke the water and I gave my thin leader one more test of strength, loading the ten weight just enough to drag the carp into net range.

The fish was a bit over thirty inches, and we estimated the weight at about twenty pounds. Even without the metrics, it was clear that I’d hit my new PB common carp by quite a bit.

The whole situation couldn’t have gone better, but I definitely wouldn’t do it like that again. For all the time and financial investments I’ve put into fly fishing, I probably should’ve been better prepared, and that’s on me. I don’t like going into a fight undergunned, for me or the fish.

But sometimes you have to just take things at face value. The ten weight/eight pound leader setup for a twenty pound carp was sketchy. But take the premeditated decision and even the win probability out of it, and you’ve got a situation with a big fish, light tackle, some mid-fight drama, and a happy ending. Just sounds like a good fishing story to me.

Muskie, Revisited

My first experience ever fly fishing for muskie took place in October 2022. It was a gray, blustery morning in northern Minnesota on a rather large river. I quickly got to firing off casts, climbing the learning curve of using a two-handed beast of a rod to launch flies that were roughly the size and color of an adult macaw. For the first few hours, my presentations to bottomless back eddies and logjam thickets were met with silence. Then, in a place like all of the others I’d thrown into that day, I caught two muskie in back-to-back casts. One of them was 47 inches and probably close to 30 pounds, and when it hit the net I experienced a sensation not dissimilar to what it must be like for your soul to leave your body. The fish remains the largest I’ve ever caught on the fly.

When I moved back from Oregon, chasing the high of landing another one of these top predators reemerged as a priority. Before I’d left the Northeast several years ago, my equally insane friends and I had just begun to investigate opportunities to find the fish near us. It was mostly research at first— hunches confirmed by field reports or networking with other anglers, but now that we were all close to our old home waters again it was time to follow up.

Long story short we were right, but my beginner’s luck had run out. I spent several long weekends this past summer meeting up with Franky, Jon, and Charlie, where we ran full day float and wade explorations into waters we’d never been to but actually ended up being successful. Muskie fishing can very much be a team effort— with the fish’s scarcity and pickiness, making good decisions and not screwing up netjobs are often helped along by multiple people, so I was just fine being around the catching. But by the end of the summer, I was very aware that I hadn’t personally hooked or landed a muskie in my first real attempt to do so since Minnesota. And that wasn’t going to fly.

So with the season drawing to a close, I made a final effort. I found one day in late October and blasted up from Boston to meet Vermont-based Franky for a day float. It hadn’t rained in weeks, and the water was low and incredibly clear. With the lack of current, flotillas of browned leaves stalled in the deep pools we wanted to fish. The wind bullied us on open stretches of river.

As someone who has fished many a bite to the bitter end, the day and conditions had every making of something that was just a little too past its prime to produce anymore. Our results so far had aligned with this theory, but as we moved towards the end of the float we saw a bit more activity. A few long dark shapes crept after our flies every so often, becoming bolder in the afternoon warmth. Finally, Franky broke the silence with a muskie out of a large logjam. It was another fish I was yet again happy to see landed, but my selfish doubts from the summer returned as we resumed our float after the release. It was looking like my place as the net man was becoming permanent.

With all of the prime spots covered, Franky suggested going up a short creek that I’d never journeyed into. He was working hard to get me on a bite, but I think we both knew that this would likely be my last shot of the season at unfished water.

The tributary was muddier than the mainstem and about a quarter of the size, but the stretch towards its confluence was deep and chock full of cover. I clipped my rod tip often on unseen sticks as I brought my fly close to the boat on the figure eight. Mid-conversation with Franky, I remember completing a cast, sweeping the rod parallel with the boat, and feeling the line flex again as it got caught in the depths. It was only when I lifted the fly to a few inches under the surface that we could see the muskie attached to it.

Just like that, my drought was broken. It wasn’t the biggest muskie around, but the suspense of the day and mysterious tug from the bottom was exactly why I had stayed obsessed with learning more about these fisheries. I have no doubt I’d be doing the same thing again next season (hopefully not the summer-long skunk part though).

Right around the next corner of the little tributary I caught another muskie, this time on an unmistakable violent eat. I couldn’t help but think of the similarities between the last day I successfully caught muskie, with a couple fish coming within a very short span of time during that moment in the Midwest. There are short bite windows and moon phases to credit here, but I also tie some of the classic muskie superstitions into this too. Anglers have their good karma fly, favorite boat drink, or lucky underwear. When it comes to muskie fishing for me, good things come in twos.

The Last Brook

It was early November. I could fish in a t-shirt. There must still be a brook trout somewhere.

Ironically, the less opportunities there were, the more research I had done on fishing. I had established lots of great native trout spots further West in Massachusetts, but with how crummy the water conditions had been I didn’t want to risk the long drive for nothing. I needed a new set of places— something closer, with the same likelihood of trout and a shorter “drive of shame” if I got skunked late in the Fall.

With a visit to the long forgotten world of internet fishing forums and a sprinkle of intuition, I settled on a handful of systems less than an hour’s drive North of town that, as of the early 2010s, had brook trout in them.

On a free Sunday, I headed up to take stock of what I’d found. I knew that whatever I saw wouldn’t be a fair assessment of what the fishing could be, since the water was incredibly low and fish weren’t as likely to be active. I was also cognizant of the fact that brook trout in some of the systems could be spawning, so I stayed out of the water and targeted areas that would hold fish looking to feed, if there were any.

For these reasons, I wasn’t exactly surprised when the spots failed me one by one. There was some great looking water in this small corner of Massachusetts, and almost every sleepy rural town had a cold, clean creek spilling in from the hills above. Most of them were just way too low to think about fishing, and I spent much of my morning and afternoon crashing through thickets and looking for more options on satellite.

During another one of these hunts for a backup plan, my eyes caught on a Google Maps geotag for a “scenic waterfall” on one of the streams I’d marked. I figured that if the falls were notable enough to have a Yelp review, they’d likely have some sort of deeper pool underneath.

No one else was in the small pull off for the trail. I made the short hike up another creek that was dishearteningly low and found the falls trickling off some exposed boulders. There was indeed a large, rocky plunge below the drop— no more than a couple of feet deep but among the best water I’d seen. I covered the spot with a small jig streamer, swinging it under overhangs and bow and arrow casting into the mist thrown up by the falling water. Finally, after just enough casts that I was beginning to lose the hope I’d held out for this hole, I picked up a fish.

There’s a few reasons why we tend, at least in freshwater, to have these last-chance wins in late Fall. Some of it may just come down to timing, being that a morning start may simply align too cold for your target species to actually be feeding. Therefore, you just end up catching fish later and in the warmest part of the day.

But if that’s true, why keep putting in full days at all? I think the uncertainty aspect of fishing that attracts us all as anglers is the same thing that gets us out earlier and keeps us out later than common sense would prescribe. It can be a thirst for knowledge, adventure, a draw outside, whatever. Just because the results say otherwise doesn’t always mean we want to stop doing what we love. And as the year slowly takes those opportunities away from us, we often hold onto it tighter.

So keep holding on. Fish if it makes you happy. Get skunked, or frozen, or maybe both. Because on one of those days when you’re out in the leafless sticks, or on an empty beach doing what everyone else is telling you not to do, you may just find something new about your craft, or even scarier— about yourself.