Sometimes, finales just don’t do the story justice. I personally thought that ending a couple years spending most days either fishing or working with Josh Czech needed more of an epic send off.

Instead, we got Central Oregon in March. The persistent chill of winter had begun to flicker with a string of warm, snowless days. It raised the water temperatures tantalizingly high enough to the point where we started making quick trips to the Middle Deschutes River, looking to time out an afternoon with the local little-fished Skwala hatch. Then it got cold, dumped snow, and got warm again, assaulting the river with meltwater and chilling the flows back into the 30s. With just a few days before I flew back East, I was suddenly faced with the uncomfortable feeling of realizing you no longer have an infinite amount of time in a place you once called home. There was no way Josh and I were parting without getting on the water one more time, so it was back out into the light flurries and gray afternoon in a Tumalo canyon, armed with floating lines and size 8 dry flies.

It certainly wasn’t amazing, but we got a few small redband to save a pre-move skunk. I couldn’t help but sadly acknowledge that I was ending an era with the conclusion of our day. It wasn’t even the last time I’d see Josh before I headed out of town, but my last fishing outing while living in Oregon felt like saying goodbye to a whole other friend.

Luckily, when you part ways with a good buddy, you plan to see them again. It would be a busy summer of new jobs and cities, but Josh and I had a standing date for when after the dust settled. And for the first time in our fishy relationship, it wouldn’t be in Oregon.

(Less) West

If I remember correctly, western Maine came up on day one of working at the shop with Josh. He’d been giving me a lecture-style breakdown of often passed over native Oregon fisheries that I would come to know well over the next few years (the Northern Great Basin and Klamath Lake, to broadly name a few), as well as his propensity to consume the most disgusting dessert flavored beers on the face of the Earth, and I felt like I needed to contribute something to the conversation. In my follow up soapbox about northern pike, striped bass, and bowfin, I also touched on a series of lake and river systems deep in a dark, mossy hemlock forest. They’re a brook trout paradise with densities that rival some of the most popular western rivers, and still home to a few giant relics of Maine’s storied angling past. This wouldn’t be my first time reminiscing about this area while living in Oregon, so when Josh’s flight landed in Boston on an early September morning there wasn’t much debate on where we’d be heading first.

We fished in Maine for two days, meticulously picking apart our chosen river run to pool, riffle to side channel. Numbers were great, although size was lacking a bit compared to the past years when I lived closer to here and fished it often. We still managed some excellent specimens from the dark waters— broad shouldered, toothy footballs that gave Josh a strong fight and a picture of our constant goal in the North Woods.

In my eyes, it was a perfect experience for someone who’d never caught a native brook trout, or had even been to New England. The hillsides were beginning to rust in early Fall colors, the weather held clear days and warm nights, and the fish were cooperating. Like wind against tide, I find there’s not many days where fishing conditions and trout seem to be on the same page this time of year. Despite not finding any monsters, I was calling it a win for Josh’s introduction to the East.

I could’ve probably stayed in Maine forever, but we had a strict itinerary to follow if we were going to accomplish all that we wanted during our week of fishing. Josh wanted a creemie, and a very old fish. We were going to Vermont.

Literally Dinosaurs!

Just like fishing Maine in the Fall, an entire week plus could easily be spent in the Lake Champlain Basin alone. There are dozens of cool native species that either don’t exist or aren’t supposed to be in Oregon that Josh could see, and I wanted to make a run at as many of them as possible. On the way down 89, Josh picked up his first native smallmouth, fallfish, and even had an ill fated shot at some landlocked Atlantic salmon that I won’t mention more of so Josh feels comfortable coming back someday. With some sightings of big pike and white suckers included in our first spot, our multispecies safari was off to a pretty good start.

No trip to a mountainous New England is complete without some classic blue lining, so I had to get Josh out on a creek I used to fish in college to show him how most brook trout exist in the region. In true early Fall fashion the stream was incredibly low, but the water ran ice cold and the brookies could still be caught with a stealthy approach.

Small stream brookies and river smallmouth are all Champlain tributary staples, but my main goal here was to put Josh on a bowfin. Fishing for these ancient predators is a truly unique experience on the fly, and the fish themselves are an incredibly interesting species for a native fish nerd. Next to a good sized Maine brookie, the prehistoric bowfin was a must catch for the trip.

Bowfin are the last surviving species of a taxonomic group that can be traced back to the Triassic. They’ve survived virtually unchanged for millions of years, drawing on their air breathing abilities and tolerance of poor water quality to quietly eke out a living through more than a couple of mass extinctions.

It’s a good thing their story is so fascinating, because fishing for them sure isn’t sometimes.

Josh and I launched the boat I’d borrowed from my good friend Franky a little before 10 AM, and we proceeded to see pretty much nothing for about five hours. In my defense, I’ve never targeted bowfin this far into September. I knew they were still haunting my usual backwater locations on the lake, but I was a little unsure of what prime time was compared to earlier in the year. The sun of an unseasonably warm fall day beat down on the boat hour after hour. Josh stood up front, ready to spot a fish he had never actually seen alive, and I poled us through the weedy flats, hoping that if I told Josh that the fish were “literally dinosaurs!” again he would keep resisting the urge to shove me into the water.

Finally, in a small clearing of the swamp, I got the reaction from Josh I was looking for all day: “Woah, stop, stop, stop.” A bowfin had swum out of a patch of vegetation on a collision course with us, spotted the boat, and stopped dead. The fish backed off, then swung around again, just in reach for Josh to get his rod tip over it and dangle his marabou streamer in front of its face. I tried to remember how I had felt the first time I fished for bowfin, jigging a fly in front of a motionless target that seemed just as confused about the fly as I had been about why it wasn’t reacting at all. Now, I knew the drill. “Just keep working it,” I coached from the back seat, “He’s gonna—” Without any prior movement, the fish snapped its head up and swallowed the fly.

Luckily Josh was even more ready than I was, and made good on his first shot after a long, long wait. I finished my guiding duties with an excellent net job, and the mood in the boat took a huge positive upswing. It was honestly the most excited I’ve gotten about a fish in a long time.

Josh’s catch began an hour or so of sudden bowfin activity. We ran into several more before dark— Some spooked, some got hooked and lost, and others just didn’t really seem to care about what we had at all. In all, the fish were not the most cooperative that day. I can’t stay mad at one of my favorite native fish, though. They are how they are. They move at their own pace. They’re literally dinosaurs!

City Slickers

The following morning I tried hard to get Josh on a shore based pike, but it wasn’t meant to be. We headed to Burlington, terrorized panfish on the Champlain waterfront, and then drove back to Boston. We were leaving some of my favorite fisheries in New England with two more full days of Josh’s visit. It felt a little wrong, but spending some city time seemed necessary to show my guest that there was more to the region than two lane country roads and outdoor-themed craft breweries that so far hadn’t impressed Josh with their tame flavorings. I also had to prove that Boston wasn’t a bad place to bring a fly rod either.

We stuck local for the last couple of days, sprinkling in fishing around various sightseeing trips and a Red Sox game. A quality several hours were spent on a favorite stretch of carp water that I had fished often over the summer. As wild as the North Woods and diverse Lake Champlain species are, I think there’s something to be said for showcasing the unique urban fishing opportunities of the populated Northeast. Josh wanted a multispecies experience on his trip, and I don’t think I’d be a good host if I didn’t show him all sides of what had to be done to make it happen close to home.

So it was off to a local riverwalk to get gawked at by pedestrians and sight fish invasive species until our arms were sore. Despite the incoming creeping chill of Fall, there were still plenty of carp around on the shallow mud flats. We even got our licenses checked by a cop in the park. In all of my years on the water I’ve only ever been checked a few times, but I swear it always happens in the weirdest, most unfishy places. Good to know Boston carp stocks are well protected though.

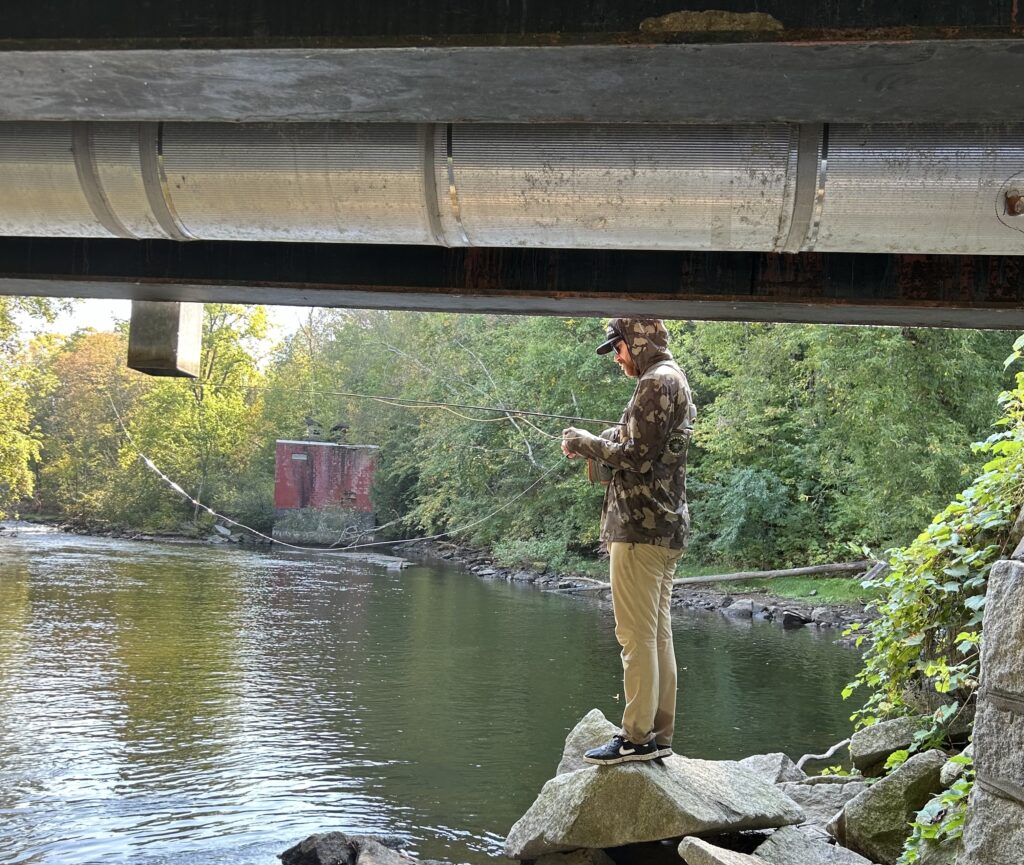

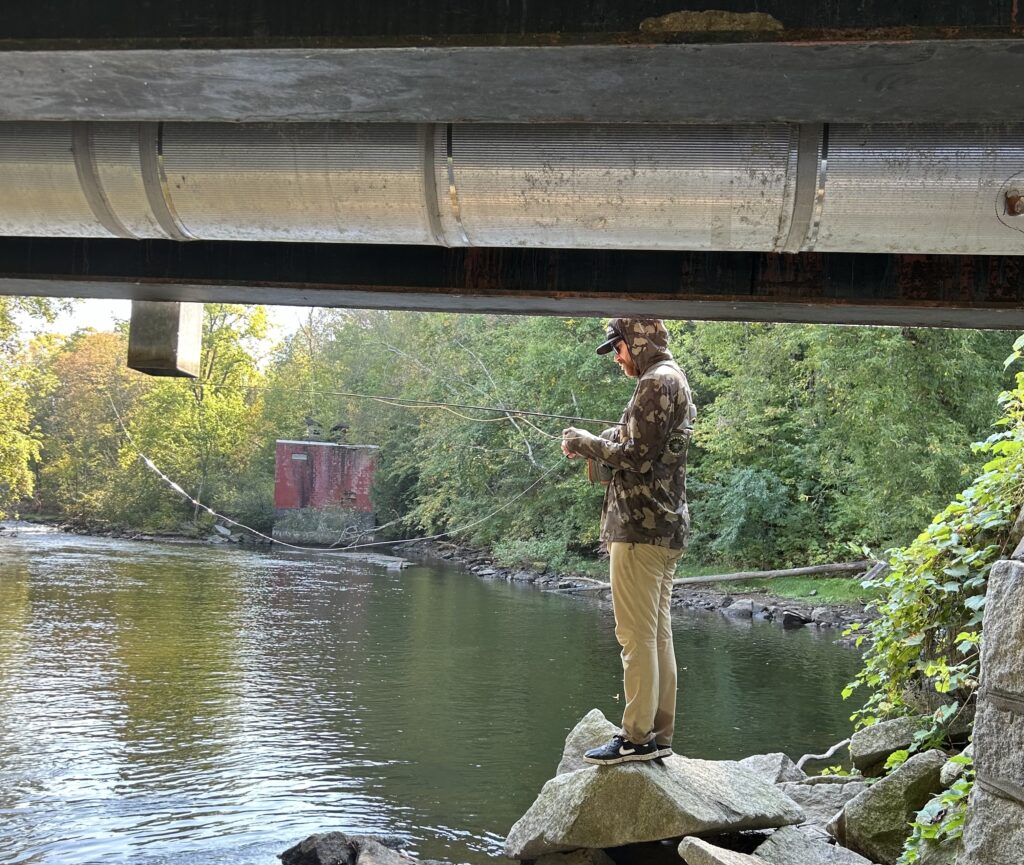

For our last day we headed an hour outside of town for sea-run brook trout. Armed with some micro jig streamers and light rods, we crept through the thick undergrowth blanketing a small tannin stream and jigged around likely holding areas. We hadn’t timed it well. The full moon tide had ballooned the lower section of the creek into a large pond, making it difficult to fish these spots the way I was used to. Still, we managed a few specimens from the relict population, including a couple of short but fat silvery fish that had likely spent time in the bay. For two native trout geeks that have spent more than enough time driving further into more remote areas and catching less, it doesn’t take much to make a day sometimes.

Of course, the company helps. I’ve been very lucky over my relatively young fishing career to make some quality friends. One of the best parts of any all-consuming passion is getting to know people who share the same interests, but I’ll throw my very biased opinion in the ring for fishing relationships being some of the best. You don’t just go hang out at a club meeting every week or so, and maybe grab a coffee after. For every hour exclusively spent on the water, there are hours more of car rides, fly tying, daydreaming, hiking, after dark and pre-dawn down times. To find people who are not just ok with but enthusiastic about doing all of the above in the pursuit of a slimy animal that doesn’t care if you live or die is rare. Josh is one of those people, but big cross-country moves mean that he’s part of a group of people who I likely won’t see much of in the near future. I’ve had to do a lot of reflecting on the obvious paradox of leaving a place and people I’ll miss dearly for a similar bundle of companions and locations.

There is only one aspect of having friends who fish that transcends experiences and distance, and that’s what you learn from them. Trading knowledge with others is an invaluable way to learn to fly fish. Josh and I have exchanged what we know for years, but I’ll always be grateful for what he showed this newcomer to Oregon. Leading with his passion, he opened up a world of endemic species, land history, and conservation sagas that I’ll now forever be chasing down the meanings of, right along with him.

When it came time to show off a highly abridged version of all the stuff I rambled about in a fly shop years ago, I tried to do it proud. If he ever wants to see more, there’s a couch and some leftover gross beers that I won’t ever drink with his name on them.